Churches with round towers are unusual. Stephen Hart suggests there are about 181 round tower churches, including the visible remnants of fallen towers, as well as others that are known about from historical records and illustrations. Most of these are in East Anglia. Norfolk with 126 has the most. There are 42 in Suffolk, 6 in Essex and 2 in Cambridgeshire. Elsewhere there are 3 in Sussex and 2 in Berkshire. Of these about 150 date from the medieval period. Their unusual shape raise lots of questions about the form and function of towers, when they were built and how they have changed over time.

Towers: their functions and evolution.

One of the main purposes of towers is to house bells. Roger Stalley in his 1999 book Early Medieval Architecture, chapter 6, discusses towers, their architecture and purpose. Neil Christie in his 2004 paper On Bells and Belltowers, origins and evolutions in Italy and Britain, AD 700-1200 argues the association between bells and Christian worship has a long history, first with small liturgical bells and later with large bells rung from towers. The origin of towers goes back to Late Antiquity but they become a common feature of church design only in Carolingian period towards the end of the C7. Built at the junction of the nave and chancel, these towers gave light and a sense of space and their position close to the high altar emphasised the main liturgical focus of the church. Two circular towers dominated the church of St Riquier built about 800.

Towers come to play a major part in the architectural form of a church. Porch entrances were built for example at the west end of churches at Monkwearmouth in North East England and Deerhurst in Gloucestershire. These towers provide a formal and impressive entrance to their churches. Later, possibly in the early Norman period, their towers (and that at Brixworth) were made taller and transformed into bell towers.

Monkwearmouth (photo by Andrew Curtis), Deerhurst and Brixworth churches

Towers sometimes constituted the major structural element of the church (turriform churches). Well known examples of late Anglo-Saxon turriform churches are Earls Barton and Barton-upon-Humber (below) where the C10 turriform church comprised tower, western baptistery annexe and eastern chancel. Bell towers become a central aspect of church architecture across Europe. Mosques also have minarets or towers from which the imam calls the faithful to prayer: the minaret of the mosque in Seville became the belltower of the catholic cathedral after the re-conquest of Spain in 1492.

Earls Barton and Barton-upon-Humber churches

The building of towers is sometimes linked to a law of King Athelstan in 937 which said that to claim the status of thegn (as in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Thane of Cawdor) landowners must have a bell tower on their land. Some towers owe their existence to a landowner’s wealth and their desire to claim thegnly status. Thegnly churches were owned privately and tithes and donations provided the owner with an income. As the Domesday Book shows, by 1086 a shift was taking place towards a system of church organisation based on parishes which encouraged the building of parish rather than thegnly churches.

Paul Cattermole in his 1990 book Church Bells and Bell-Ringing: A Norfolk Profile and Richard Harbord in an article Bells and Belfries in the Round Tower, June 2010 discuss the evidence for early bells and bell towers. The large sound windows or belfries in early churches such as Bessingham, Aslacton and Great Dunham suggest the importance of bells and bell ringing.

Belfries of Bessingham, Aslacton and Great Dunham

From the middle of the Norman period towers become more common and their bells were rung for a variety of purposes: calls to service, prayers, to mark the hours, funerals, weddings & festivals, accompany processions and commemorations, for assemblies and warnings and even Royal occasions, with different modes of ringing for different occasions. Some towers had stairwells to provide access to the bells (as with the round turrets at Norwich cathedral).

Towers also provided space for accommodation of clergy, storing church vessels and as part of the liturgy and processions. But ‘towers were and are visible social symbols, forming points of recognition and foci for congregation and for wider communities’ (Christie, 2004). They could serve as landmarks and guides to mariners (eg churches along the north Norfolk coast). In the early Middle Ages churches and their towers were almost the sole stone buildings in their locality: they denoted substantial investment as well as visible devotion. Donations, grants and endowments served to enhance the standing of the church and their donors and stimulate competitiveness between them.

Defensive role: it has been suggested that towers have a defensive role. While East Anglian towers may have served as observation points and could ring warning bells, there is little evidence of free standing towers. Furthermore they were built after the main invasions. Many churches in East Anglia are built on higher ground but their position may have been chosen to increase the visibility of the church and its tower in the landscape. The round towers in Ireland and Scotland, in contrast, do seem to have built with defence in wind: they are taller and more slender than the round towers of East Anglia. Richard Harbord revisits the notion of towers as defensive structures in an article in The Round Tower December 2011.

Norfolk Heritage Explorer has an excellent guide about how to investigate a church (http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record?tnf1235)

Round and square towers.

There are both early round and square towers in East Anglia. Square early towers (built before c1150) include Great Dunham, Hethel, Newton-by-Castle Acre and Little Bardfield, Suffolk. The towers at Great Dunham and Newton-by-Castle-Acre are central like those at Earls Barton and Barton-upon-Humber. Excavations at the Anglia Television site at Norwich found the outline of a timber C10 or early C11 Saxon church with a post hole at the crossing which the archaeologists suggest was a lantern tower or belfry (See Digging under the doorstep published by Norfolk Museums Service 1983 and Brian Ayers 2009 book: Norwich: Archaeology of a Fine City, chapter 2).

Square towers at Newton by-Castle Acre, Little Bardfield, Colchester and Corringham, Essex

Round towers. The East Anglia tradition of early round towers contrasts with that of most regions of England, including Lincolnshire. Examples of early East Anglian Round Towers include Roughton, Forncett St Peter, Beeston St Lawrence, Bessingham, Bexwell, and Appleton. See the Listing of Round Towers page.

Early round towers at Great Dunham, Hethel, Roughton, Forncett St Peter, Beeston St Lawrence & Appleton

Why were round towers common in East Anglia? Why did people in East Anglia decide to make a tower round rather than square? There are no written accounts which throw light on this but a number of reasons have been suggested.

Stephen Hart amongst others suggests that round towers became popular because they were relatively easy to build with the materials available locally. In East Anglia there is little good building stone and flint is the most widely available material. Flint occurs as comparatively small and knobbly individual stones which cannot be easily cut, worked or dressed. When set in mortar flint can create handsome walls and buildings but it does not lend itself so easily to making quoins at the corner of buildings. While round towers avoided the need for quoins or corner stones, quoins were still required for the corners of the nave, as at Worthing. Finding good pieces for corners may have been very time consuming. Sometimes (eg at West Dereham or Roughton) large blocks of iron bound conglomerate (IBC) were used in the walls of round towers which could have been used as quoins, had the builders so wished.

Use of large blocks of IBC at West Dereham and Roughton

While a round tower may have been easier to build, positioning a round tower next to the straight wall of a nave was still a skilled task: a quadrant pilaster (a fillet of masonry which fills the space between the tower and the western wall of the nave) was used in about a quarter of churches to fill the gap (as at Thorpe-next-Haddiscoe). Flints were sometimes used decoratively, as with the vertical strips at Thorpe-next-Haddiscoe and the recessed blind arcading at Tasburgh and Thorington.

Vertical strips at Thorpe-by-Haddiscoe and arcading at Tasburgh and Thorington

Round towers as an earlier form of tower. It is sometimes argued that round towers were an early form of tower, part of Anglo-Saxon or pre-conquest building tradition which was later replaced by square towers. However, there are examples of early square towers. And round towers continued to be built throughout the medieval period.

Whatever the practicalities and costs of building a tower, there was always an element of choice or fashion in the shape of a tower. Some round towers were later replaced with square towers, perhaps because square towers were considered more attractive and prestigious, or because they were more convenient for hanging several bells. It is difficult to fit a bell frame which could house more than one or two bells into a round tower. Evidence of round towers which were replaced by square towers include: Martham (footings of a round tower were found when work was done in the tower in 1999); Redenhall (Victorian restorers found evidence of a round tower); Denton (an application to construct square tower in 1698 to replace a round tower which had collapsed: Paul Cattermole 1990 p80); Carleton Forehoe (article by Richard Harbord in The Round Tower December 2014); Houghton on the Hill (base of round tower found during excavations in 2000 see Richard Harbord’s article December 2007). Round towers survive, as time capsules, in small rural villages where there was not enough money or a sufficiently wealthy donor to rebuild the tower.

There are a number of stories and legends about round towers. One of the most fanciful is that round towers were originally built as wells but that a great flood washed away the ground around them, leaving the well walls sticking in the air. The resourceful local people then built their churches against them, using the wells as bell towers. The East Anglian coast suffers from erosion, giving rise to strange relics of lost settlements: a cliff fall at Pakefield, Suffolk in 1956 left a brick lined well standing on the beach. Many churches and settlements have been lost through coastal erosion including the round tower church at Eccles next to Sea (see The Round Tower, December 2008 & December 2015).

Where might East Anglian round tower builders have gained their inspiration?

Roundness. As Nick Groves suggested at RTCS Study Day (The Round Tower December 2012) there is a long prehistoric tradition of ‘round’ ritual places such as round burial barrows and stone circles. The Greeks and Romans built round as well as the more common rectangular buildings including the Greek tholos buildings of Temple of Athena at Delphi (380-360BCE) and Polkycleitus at Epidaurus and Roman Temple of Hercules (C2BC) and C1 pre-Christian Pantheon in Rome. More locally there is the Pharos or lighthouse at Dover and the towers or bastions of the Roman fort at Burgh castle several of which were still standing when Burgh church with its round tower was built close by.

Pharos, Dover; Burgh Roman Fort, Round Temple, Delphi, Pantheon photo by Clayton Tang

Christian models of round structures in Europe include Charlemagne’s chapel in Aachen built c800CE, several early brick towers in Ravenna in Northern Italy including San Apollinaire Nuove, Sant Apollinaire in Classe and Orthodox Bapistry (See an article in The Round Tower September 2008). The famous round tower at Pisa was built in 1170s. The C12 campanile or Torre Fenestrelle at Uzes near Nimes in southern France is one of the few round towers in France.

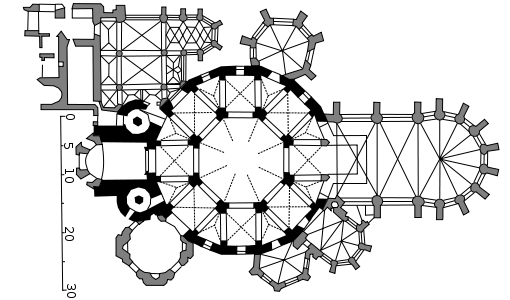

Plan of Aachen, Leaning tower of Pisa, Torre Fenestrelle, Uzes

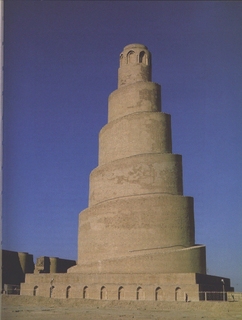

Minarets have also been suggested as possible models for round towers. However, it is generally accepted that minarets were influenced by early square church towers in Syria. Further east there is a Sassanian tradition of round structures eg the round Zoroastrian temple of the winds at Yadz (Iran), minaret of Samarra (Iraq), Manar at Mujola and Kalyan in Bukhara.

Tower of the winds, Yadz, Samara, Manar at Mujola and Kalyan in Bukhara

The round belfry is also found in Ireland where it is described in the local annals as bell houses. They first appeared in C10, usually with a subtle ‘batter, tapering slightly and surmounted by conical roofs of stone.

There are about 30 Northern European round towers in northern Germany, Poland and southern Sweden bordering the Baltic Sea. These northern areas were late converts to Christianity and most of the round tower churches are dated to the C12th, although as Stephen Heywood suggests, the earliest, at Heeslingen (now demolished), may have been built in the early 11th century. Hammarlunda in Sweden closely resembles Hales church. These round towers are evidence of a North Sea culture and of trading links between the Baltic regions and the East Anglian ports (Stephen Heywood (2013) in East Anglia and Its North Sea World in the Middle Ages).

Hammarlunda church

More locally one model for round towers might be the abbey at Bury St Edmunds which had a Rotunda or sepulchre chapel of the martyred king Edmund (dated about 1020 in the reign of the Danish King Cnut) which was cylindrical in shape, and supposedly based on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (see Richard Harbord in The Round Tower June 2004 and June 2007). Stephen Heywood (2012) points to the turrets of the radiating chapels at Bury and also at Norwich cathedral as other possible sources of inspiration for round towers, perhaps a form of ‘architectural homage’ when the copying of details from a mother church imparted special qualities to the copied building (In Architecture and Interpretation (eds) Jill A Franklin, T A Heslop and C Stevenson). Richard Harbord considers Wilfrun’s octagonal at Canterbury (1050 – 1066) as a possible inspiration (The Round Tower, March 2008). The Templars churches in Cambridge and London were circular in form.

How old are round towers? Dating Round Towers.

There has been considerable discussion and disagreement about the age of round towers. The relatively unsophisticated design of many round towers, the use of what appear to be Saxon features, and the absence of round towers in Norman or French Romanesque churches have lead some writers to suggest that they date from Saxon times before the Norman conquest in 1066. The founder of the Round Tower Church Society, Bill Goode, suggested that a substantial proportion of round towers were of pre-conquest date. However, Stephen Hart and others argue that many round towers are of a later date: Stephen believes the evidence suggests that only about 27 of the 180 are likely to be Saxon, with another 12 or so dating from the Saxo-Norman overlap period during which some elements of Saxon technique and style persisted in early Norman work: 44 are probably Norman and about 80 are post-Norman medieval, with round tower building continuing, concurrently with square towers, well into the fourteenth century and possibly the fifteenth. The rest are of uncertain date or later.

Dating towers (and much else about church building) is usually a complex task. There are no records and so no hard evidence about when towers were built or when changes were made to church architecture. In the absence written records, attempts at dating towers and their churches has tended to focus on style and the use of materials, on features such as the shape and decoration of belfry openings. But customs and building practices often change slowly, so for example a Norman lord building a Norman church is likely to have employed local builders steeped in Saxon building traditions. So a ‘Norman’ building may show ‘Saxon’ characteristics, adding to the difficulties of making an accurate dating.

While many round towers were modified in the course of their history, most often by the addition of octagonal tops, round towers continued to be built to the C14. There are also more recent examples including: St Stephens, Higham Suffolk built in 1891 to a design by Sir Gilbert Scott, who is perhaps best known as the designer of the Albert Memorial. Perhaps the most recent is St Felix in Haverhill opened in 2012. The Society is always pleased to hear of new round tower churches.

Materials used in building towers.

Stone is always expensive because in East Anglia it needs to be bought from a distance and then shaped or ‘dressed’ by masons. When available, stone was frequently used as quoins or cornerstones. However, even when stone could be found, a cheaper way to build a flint church tower was to make it round and hence avoid the need for corner stones.

Flint and other building materials.

Flints have been used in different ways over the centuries. Many towers are faced with ‘as-found’ flints of irregular shapes in various shades of grey, white, black and brown, extracted from their parent chalk strata or gathered from the fields, local deposits or the seashore, and set in plenty of mortar, randomly or coursed. Some are faced with smooth rounded cobbles, laid uncoursed or neatly coursed in even rows. A few towers are built of carstone (a cretaceous brown sandstone that outcrops in West Norfolk) or puddingstone (a coarse dark brown material containing flint fragments found in shallow localised deposits) eg Bexwell and West Dereham, while some towers show an uneven mixture of flints and puddingstone or pieces of Roman bricks as at Burgh Castle. There is an article about carstone and conglomerate in the March 2013 edition of ‘The Round Tower’ and an article in the Round Tower in 2002 is also available: Carstone and Ferricrete by Stephen Hart.

Tower at Bexwell (photos taken by Stephen Hart) and Bessingham.

Knapped flint: some buildings in East Anglia have walls faced with knapped flint, a well-known example being St Andrew’s Hall in Norwich. Knapped flints are cut to a flat face showing their lustrous interior, and may be squared or trimmed to fit together closely. This expensive technique was not used until after most of the round tower churches had been built, but knapped flints do occur in a few later medieval round towers and in some octagonal belfries added later. They are used randomly at Tuttington, in decorative bands at Cockley Cley and wholly face the ruined tower at Wolterton. Knapping, cutting and trimming flints is a highly skilled task and expensive, and so is found mainly in churches with rich patrons. The Victorians sometimes used fine knapped flint in their restoration of medieval churches, as for example the squared knapped flint at Blunderston.

Fine Knapped flint at Blundeston, Eccles and Quidenham.

Fine Knapped flint at Blundeston, Eccles and Quidenham.

When stone was available, flint and stone were sometimes used to create complex decorative effects, as flushwork and as dedications. Brick including Roman brick was used in churches such as Fritton and Burgh Castle (a short distance from the Roman fort). Once brick started to be made it was often used. Stephen Hart examines the use of bricks in Round Tower Churches in September 2013 edition of The Round Tower. Stephen Heywood wrote on the use of reclaimed Roman building materials in Norfolk Churches’ in The Round Tower in September 2002. This article can be viewed by clicking Reclaimed Roman materials.

For more information about flint and flint flushwork, see Flint Flushwork: a Medieval Masonry Art by Stephen Hart, published in 2008 by The Boydell Press.

Richard Harbord has also written about materials used in churches in The Round Tower September 2010. This can be viewed on the website, via The Round Tower page.

Stone was used more frequently after the Norman Conquest, brought from places such as Barnack near Stamford and Caen in Normandy (both were used at Norwich cathedral). Stone was sometimes used to make repairs in walls built at an earlier time.